Less Common Meroplankton

Introduction

This section is not a taxonomic group. It is a mix of different organisms which are meroplankton, they are only plankton for a portion of their lives. Life cycles can be complex with each stage looking very different. Sometimes the same animal can be found in samples in multiple life stages, each looking different. It is important to be aware of this to help with identification. All animals in this section are plankton as larvae.

Crab

When it is time for crabs to mate, they release pheromones (chemical smells) to signal it is mating time, this can be from the female or the male depending on what species it is (Castro, 2013). When a male and female find each other they ‘hug’, the male will wrap is claws and legs around the female and hug her for several days! During this time the eggs are fertilized.

Crab eggs will hatch a larvae we call zoea, this is just a name for a larvae that is plankton. There can be multiple zoea stages, which will develop into a megalopa (another planktonic larvae!) (Johnson & Allen, 2005). After this stage they become the adult crab, we recognize. In our samples we can see the zoea and megalopa of crabs, they differ between species, but we can recognize some key features.

To the right is the life cycle of the blue crab “Callinectes sapidus“. Stage 1 shows the eggs laid by the female. Stage 2 shows the zoea that the eggs develop into. Stage 3 shows the megalopa stage. Stage 4 shows a juvenile crab, at this point the crab is no longer plankton. Finally, stage 5 shows the full-grown adult crab.

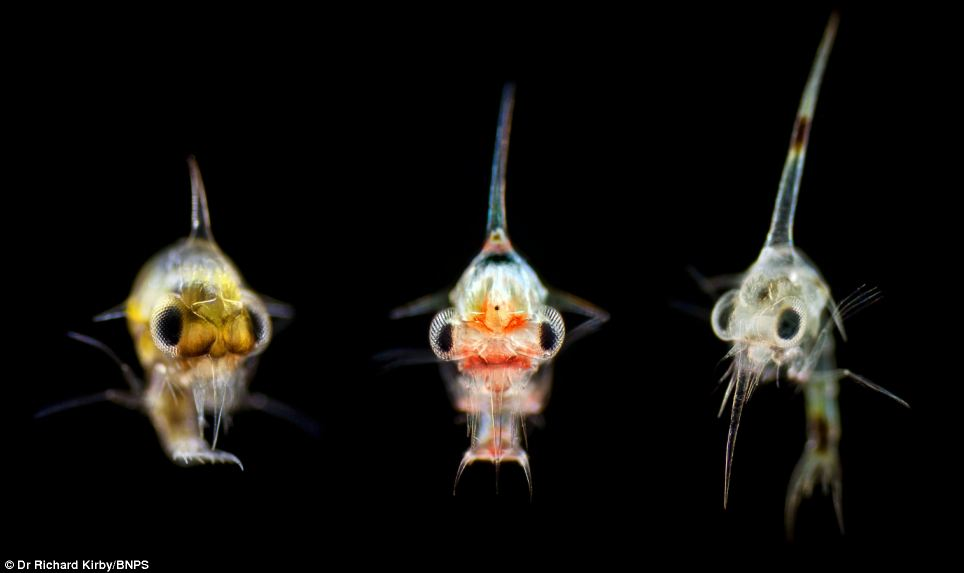

Zoea have large eyes which can sometimes be spotted if they are facing the right direction. All have a slim, segmented body and 2 or 3 spines, however these are not always visible depending on what direction the zoea is facing. This is important for all organisms, but especially zoea, be mindful that they can be pointing in different directions. This may explain why they look strange or a feature is missing!

Mantis Shrimp

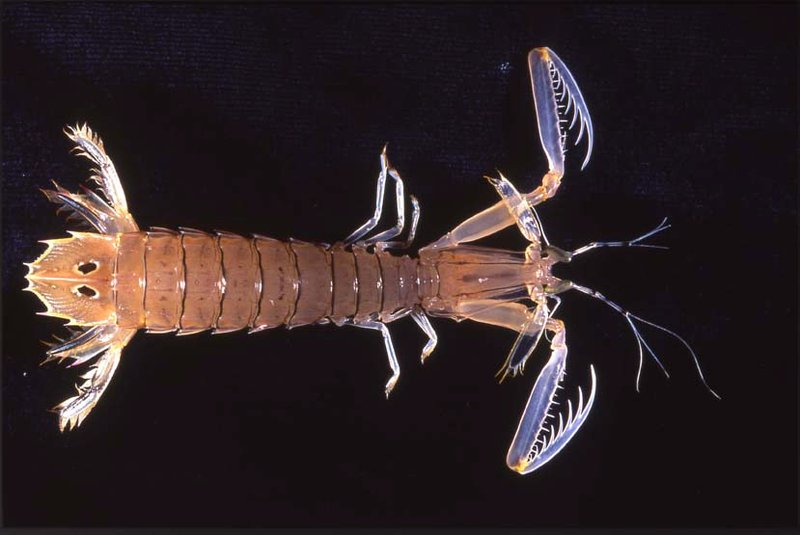

Mantis shrimp are different to true shrimp and can be called stomatopods. This name comes from ‘stoma‘ meaning mouth and ‘pod‘ meaning foot. They spend roughly the first 3 months of their lives as plankton before developing into their adult form.

Mantis shrimp are carnivores and have special appendages used to attack and kill their prey by spearing or stunning them (Cronin, 2006)! The way these appendages are adapted vary slightly with species, but all have the same goal of capturing prey.

Mantis shrimp have a similar structure to a praying mantis, which can be useful in identification. The have slender bodies, with appendages attached to it. They have eyes on stalks which can usually be seen, and their predatory arms, which almost look like clubs. They can be found with their bodies straight or with their body curled up into a ‘U’ shape.

Echinoderm

Echinoderm comes from ‘echino‘ meaning spiny and ‘derm‘ meaning skin. This group includes creatures like sea stars, sand dollars and sea urchins.

Each animal will look slightly different but echinoderms are not common in the samples and most have a similar look to them. There are two main groups called pluteus and bipinnaria (Zooplankton.nl). Pluteus is more common, usually made up of eight arms supported by long needles.

Echinoderm larvae have hairs all over their bodies, these vibrate and help them swim to prevent sinking!

This website has some cool videos of different echinoderm larvae under the microscope

Echinoderm larvae (pluteus) can be identified by the spiny structure. There are not many features, the key thing to focus on are the long spines!

Fish

Ichthyoplankton are the eggs and larvae of fish, at this stage they are plankton but when they grow to their adult forms they become nekton. This change of plankton to nekton usually occurs halfway through their development (NOAA, 2023).

Most larvae are carnivores, even if they eat plants as an adult, and feed on other, small zooplankton. It is a challenge for fish to survive the larval stage. They have no control over where they go and have many larger predators that like to eat them (Steele, 2001).

As fish have a variety of appearances, so can their larvae. The shapes and sizes can vary but there will be visible fins, and the overall body shape can be recognized as similar to a fish. By looking at the overall organism, and identifying fins, you can identify it as a fish.

Sea Anemone

Sea Anemone’s belong to the group Cnidaria, this is the same as jellyfish! They begin as a planula larva, very small planktonic larva, before settling and growing into an adult anemone which does not move. The larvae have small projections called cilia which help them move through the water but are not strong enough to move against currents.

Some species can produce toxins or stinging cells to help protect them as they are very vulnerable in this stage, these are called nematocysts. All these guys want is to find a suitable place to settle and grow into their adult form! They are a meroplanktonic species as only a portion of their life is spent as plankton.

They have a dark, cylindrical body with many appendages that look like tentacles. They can look very similar to sea stars, and if you can identify this shape, it is an anemone larva.

Flash card practice

References

Ardovini, R. (2022). Astropecten irregularis (Pennant, 1777), Capo Vaticano, su fanghi a −200 m [Photograph]. In Astropecten irregularis [Figure 2]. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Roberto-Ardovini/publication/360335681/figure/fig2/AS:1151611602771969@1651577010680/Astropecten-irregularis-Pennant-1777-Capo-Vaticano-su-fanghi-a-m-200_Q640.jpg

Australian Museum. (n.d.). [Photograph of marine organism]. Retrieved May 16, 2025, from https://media.australian.museum/media/dd/images/Some_image.width-800.c43bb49.jpg

Castro, J. (n.d.). Animal sex: How crabs do it | Animal mating & behavior. Live Science. Retrieved April 1, 2025, from https://www.livescience.com/36972-animal-sex-crabs.html

Cronin, T. W. (2006). Stomatopods. Current Biology, 16(7), R235–R236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.014

Daily Mail. (2014, August 12). [Photograph of deep-sea marine organism]. https://i.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2014/08/12/article-2722690-207794E700000578-664_964x573.jpg

Houde, E. D. (2001). Fish larvae. In J. H. Steele (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (pp. 928–938). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1006/rwos.2001.0026

Johnson, W. S., & Allen, D. M. (2012). Zooplankton of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts (2nd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

NOAA Fisheries. (2023, January 31). Frequently asked questions about ichthyoplankton | NOAA Fisheries (West Coast). https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/west-coast/science-data/frequently-asked-questions-about-ichthyoplankton

Science News. (2021, March 30). Flounder fish larva [Photograph]. https://www.sciencenews.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/033021_dr_fish-larvae_inline_flounder_live.jpg

Shutterstock. (n.d.). [Thumbnail image of marine organism from stock video]. Retrieved May 16, 2025, from https://ak.picdn.net/shutterstock/videos/1087395791/thumb/1.jpg?ip=x480

Zooplankton.nl. (n.d.). Echinoderms. Retrieved April 1, 2025, from https://zooplankton.nl/en/diversity/echinoderms/